1. Defining ethnic regional autonomy

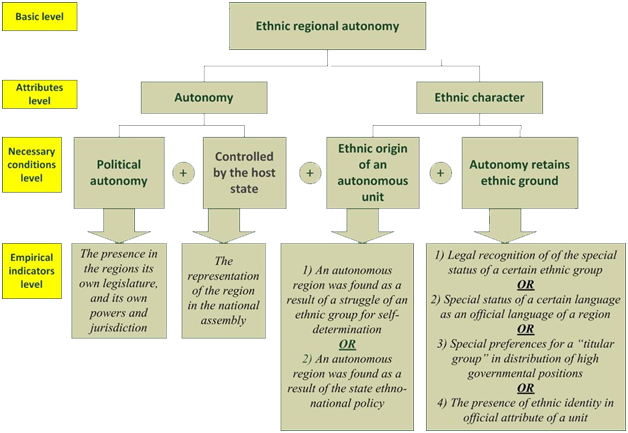

In the framework of the project, ethnic regional autonomy (ERA) is defined on the ground of essential characteristics (attributes)– territorial autonomy and ethnic character of a sub-national unit.

ERA is an administrative-territorial unit of the first sub-national level, which is constituted on an ethnic basis and within the priority of the national state has a sufficiently high degree political self-government.

Figure 1. Conceptual structure of ‘ethnic regional autonomy’

Empirical criteria (necessary conditions) and operational indicators for defining of sub-national unit as ERA:

1) Autonomy

Territorial autonomy is assumed that sub-national units enjoy self-government (self-rule); at the same time, autonomous sub-national units are the parts of their host (principle) states, not independent entities. The scope, the content, and the form of territorial units’ self-governance differ significantly from case to case. Therefore two criteria are introduced for the definition of territorial autonomy:

1.1) Region has political autonomy

Operational indicator of political autonomy - the presence in the regions its own legislature, and its own powers and jurisdiction

This distinguishes political autonomy from administrative autonomy, which is a result of of delegation of executive / administrative authority to lower levels of government (Benedikter, 2009: 11; Wolff, 2010: 10).

1.2) Region is included in national politics and the host state is able and capable to control the sub-national units

Operational indicator – institutionalized representation of a region in the national legislature

That is why we do not consider as autonomies ‘associated states’ – numerous unincorporated organized territories of the USA, the British overseas territories, etc., which are independent in their domestic affairs (Lapidoth, 1997: 54-55). Similarly, the so-called ‘de-facto states’ and regions of ‘failed states’ do not meet with this criteria even if these units are formally (legally) recognized as the parts of the respective state by the international community (like, for example, Abkhazia in Georgia).

2) Ethnic character of a sub-national unit

Ethnicity is understood in social constructivist way as a social categorization based on subjective belief in “common origin” or “common descent” of group’s members, regardless of what feature provide such a belief (Wimmer 2013: 7; Ghai 2000: 4; Horowitz 1985: 17-18). Two criteria are introduced for the definition of Ethnic character of a sub-national unit:

2.1) Ethnic origin of an autonomous unit: historically, ethnicity was a ground for granting autonomy to the region (Anderson, 2016: 18; Ghai and Woodman, 2013: 2).

Two empirical indicators have been developed in order to capture this criterion:

- ERA is the result of the struggle of an ethnic group for self-determination. In other words, autonomous status represents a compromise between self-determination claims and maintenance of the state integrity;

- ERA is the result of the implementation of top-down “ethnonational policy”

2.2) Ethnic character of autonomy remains up to date.

Empirically, current ethnic status of an autonomous region can be identified by one of the following indicators:

- legal recognition of the special status of a certain ethnic group as a “titular ethnic group” in the region.

As a rule, “titular ethnic group” is recognized as “distinct nationality” (Ganguly and MacDuff, 2003: 3-4) while autonomous region is still perceived as “the homeland of the definite ethnic group” (Roeder, 2014: 93); - the presence of ethnic identity in official attributes of a unit (ethnonym in the title of a unit, ethnic symbols in flag, emblem, etc.);

- special status of a certain language as an official language of a region

- special status of a certain language as an official language of a region

The term “titular ethnic group”, although not official, quite successfully grasps the ethnic character of the constitution of autonomy, especially in relation to another term - Staatsvolk, "state-forming" or "dominant in the state" ethnic group (O’Leary, 2001: 285).

2. List of ethnic regional autonomies

Political autonomy of the subnational units can be found both in federal and unitary states, hence, it is useful to think of some unitary states as the “federacies” in Daniel Elazar’s terms where “a larger power and a smaller polity are linked asymmetrically in a federal relationship” (Elazar 1994: xvi). Consequently, empirical criteria of ERA are applied for unites of the first sub-national level with special status in unitary states and all units (entities) of the federations. In contrast to federacies, in federations, the principle of federalism is applied to all entities of the federations. Therefore, federation’s provinces have political autonomy by definition; all we need in these cases is to check for their ethnic character. In this regards a useful distinction can be made between “territorial” and “ethnic” federations, where “at least one constituent territorial governance unit is intentionally associated with a specific ethnic category” (Hale, 2004: 167-168).

In sum, the full list of ethnic regional autonomies (140 cases), which exist at present or ceased to exist in the beginning of XXI century, has been composed.

It has to be taken into account that ethnic boundaries and the very nature of ethnicity is a socially changeable and contentious phenomenon. Since ethnicity is a very strong sentiment, actors struggle over which social boundaries should be considered as ethnic lines, especially if ethnicity becomes politically salient. Consequently, though in most of cases one can observe any dominant and legitimate perception of ethnic categories and ethnic boundaries shared by the members of a society there are some cases without conventional perception of what social features are considered as ethnic lines. Thus, Adjarians in Georgia, Sicilians in Italy, Zanzibaris in Tanzania and Bouganvilleans in Papua New Guinea are very disputed cases for their interpretation in ethnic sense. It means that though there is no doubt that all these autonomies are strongly connected with these groups’ identity, we cannot be sure that it is an ethnic identity.

The second source of ambiguity is rooted in complexity of the process of the creation of some autonomies. Undoubtedly, granting autonomy is caused by the combination of the reasons; and in some cases our empirical indicators for the identification of ethnic origin of an autonomous unit – struggle of an ethnic group for self-determination and the implementation of top-down “ethno-national policy” – don’t allow making a clear decision.

Therefore the list of ERA is divided in to two parts – “core list” and “border-line list”. While the ERAs from the “core list” fully accord to all the criteria of ethnic regional autonomies, 16 autonomies included in the “border-line list” are ambiguous cases.

3. Balance in inter-ethnic relations

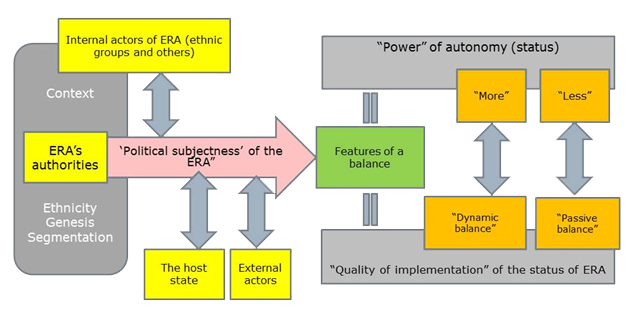

From the view of institutional approach, ethnic regional autonomy has been theoretically understood as a complex of institutional arrangements, in which respected preferences are fixed. In their combination, they form the status of autonomy. Institutional arrangements emerge as a result of interactions between actors with different preferences. The substantial idea of ERA is to achieve and maintain a balance of these various preferences. Two dimensions can be distinguished: interactions between regional autonomy and the central government (‘the center – region – titular ethnic group’) and interactions within autonomy (‘region – ethnic groups’). In the first dimension, autonomous regime allows finding a balance between ethnic demands for self-rule and the integrity of the state. The second dimension concerns a balance between the preferences and interests of different ethnic groups living in the region.

Based on these assumptions, the concept of a balance in interethnic relations has been exposed into an integral theoretical scheme. A balance presupposes that the actors involved in interactions continue to interact with each other in the framework of conventional ways and procedures even if they have opposed interests. The balance is the situation of the existence and maintenance of credible commitments, which assign a framework for predictable and stable interaction concerning the status of autonomy between the actors involved. The balance is the situation of the existence and maintenance of credible commitments, which assign a framework for predictable and stable interaction concerning the status of autonomy between the actors involved.

Figure 2. Conceptual – theoretical scheme

The dynamic of interactions around ERAs is caused by both variety of contextual factors and special features of autonomies. Though all the cases from the list of ERA share common attributes (territorial autonomy and ethnic character), they demonstrate a huge variety in their characteristics, which has significant influence on the functioning of ethnic regional autonomies. In different contexts, different problems are on the agenda of interethnic relations; the status of ERA, the scope and content of preferential policies varies significantly. This means that in different cases, various mechanisms of interaction are demanded to successfully maintain a balance in interactions around ERAs.

4. Variables and data for comparative studies of ethnic regional autonomies

Comparative analysis of ethnic regional autonomies is based on different variables - some characteristics of ERAs. The set of variables depends on the goal of the research

1) general characteristics of the host state: the size of the territory, the population, economic indicators, etc.;

2) general characteristics of the ERA: the size of the territory, the population, the year of establishment, economic indicators, etc.;

3) ethnic composition of the host states: indices of fractionalization, polarization, segregation, inequality, etc.

4) ethnic composition of the ERA: characteristics of the titular ethnic groups in ERA as well as the dominant ethnic groups (“Staatsvolk peoples”) in the respective countries, the shares of these groups in the population of the country and autonomy, etc.;

5) political and institutional background of the host states, which is important for the autonomy: political regime, system of government, electoral system, composition of national legislature, representation of ERA in national parliament and government, etc.;

6) political and institutional background of the ERA: system of government, electoral system, composition of regional legislature, special features of the regional party system, etc.;

7) power od ERA and preferential policies concerning ERA and ethnic groups, especially in the sphere of linguistic policy;

8) level of conflict in relations on different dimensions: а) between ERA, titular ethnic group and the central government; b) between ethnic groups within ERA.

Quantitative data on these parameters are contained in Ethnic Regional Autonomies Database (ERAD)that includes a wide range of information (approximately 150 variables) on all ethnic regional autonomies around the world, which exist at present or ceased to exist in the beginning of XXI century. The data are presented in the ‘autonomy-year’ format for the period from 2001 to 2015.

Qualitative descriptions of all the ERAs are presented in the Atlas of Ethnic Regional Autonomies in the form of ERAs’ profiles.

Project results (publications, analytical report, etc.) are presented in the section «Publications».

Anderson L. (2016) Ethnofederalism and the Management of Ethnic Conflict: Assessing the Alterna-tives // Publius: The Journal of Federalism. № 1.

Benedikter T. (2009) Solving Ethnic Conflict through Self-government: a Short Guide to Autonomy in South Asia and Europe. Bolzano.

Elazar D. (1994) Federal Systems of the World: a Handbook of Federal, Confederal and Autonomy Arrangements. Harlow.

Ganguly R., MacDuff I. (2003) Ethnic Conflict and Secessionism in South and Southeast Asia: Causes, Dynamics, Solutions. Thousand Oaks.

Ghai Y. (2000) Autonomy and Ethnicity: Negotiating Competing Claims in Multi-Ethnic States. Cambridge.

Ghai Y., Woodman S. (2013) Practising Self-Government: a Comparative Study of Autonomous regions. Cambridge.

Hale H. (2004) Divided We Stand: Institutional Sources of Ethnofederal State Survival and Collapse // World Politics. № 1.

Henders S. (2010) Territoriality, Asymmetry, and Autonomy: Catalonia, Corsica, Hong Kong, and Tibet. New York.

Horowitz D. (1985) Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley.

Lapidoth R. (1997) Autonomy: Flexible Solutions to Ethnic Conflicts. Washington.

O’Leary B. (2001) An Iron Law of Nationalism and Federation? A (Neo-Diceyian) Theory of the Necessity of a Federal Staatsvolk, and of Consociational Rescue // Nations and nationalism. № 3.

Roeder P. (2014) Secessionism, Institutions, and Change // Ethnopolitics. № 1.

Wimmer A. (2013) Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. New York.

Wolff S. (2010) Approaches to Conflict Resolution in Divided Societies // Ethnopolitics Papers. № 5.